Welfare Fraud Hysteria

If individuals are seen as selfish, systems will be designed with this characterisation in mind.

We are told only individuals who contribute to society should have access to the welfare state. It seems logical that exclusively good working people should expect compensation for their efforts from the state. The issue is that this thesis, when coupled with current assumptions of human nature, creates societies that aren’t all that nice.

The presuppositions underlying the dominant view of humanity are summed up by Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie Wall Street: “Greed, in all of its forms—greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge—has marked the upward surge of mankind.” It seems irrelevant that Michael Douglas, the actor playing Gekko, has declared his character the story’s villain. Humans are inherently selfish. Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Such is the rallying cry of our times.

If individuals are seen as selfish, systems will be designed with this characterisation in mind. For example, it was revealed in 2019 that the Dutch tax authorities had embedded racial profiling as a “risk” indicator in a self-learning algorithm to identify likely cases of child benefits fraud. As a result of a negative view of humanity and institutional bias, ethnic minorities were falsely accused of fraud by the Dutch government at a disproportionate rate.

Chermaine Leysner, born in the Netherlands with Surinamese roots, received a €100,000 tax bill in 2012 after being falsely accused. It took her nine years to get the mistake sorted, driving her into depression and burnout. “I had times that my little boy had to go to school with a hole in his shoe,” Leysner said in an interview—a damning indictment of the country with the world’s 10th highest GDP per capita.

It is easy to forget that a welfare budget is more than numbers in neat infographics or Microsoft Excel sheets. Cutting costs should never be prioritised over human dignity.

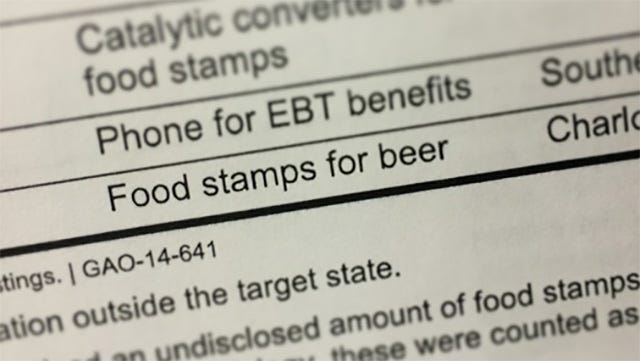

The fact is that the vast majority of people are not cheaters. Studying welfare fraud is notoriously difficult due to a lack of data. However, a 2018 US Congressional Research Service report presents the following conclusion: For every $10,000 paid in benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), $11 has been overpaid because of fraud. For reference, the IRS estimates that, for every $6 owed in federal taxes, $1 remains unpaid because of tax evasion or fraud. A stunning difference.

Yet, based on how these issues are framed in political discourse and the media, one would think the figures are reversed. Immigrants and the unemployed are presented as lazy and, worse, as indulgent welfare addicts, bleeding the state coffers dry to furnish their lavish lives. The remedy? Incentivise work. Or, rather, make it so uncomfortable for the people on welfare—usually society’s most vulnerable—that they will have to choose between work and poverty.

In Sweden, where I now live, the ultra-right-wing government and the Social Democrats follow the so-called “Arbetslinjen” (The Work Line), seeking to incentivise people to work by making their lives more precarious. Consequently, Swedish social programmes are being systematically dismantled. Whatever it takes to defeat the welfare leeches and get those rascals back to work.

When looking at the numbers, such a strategy appears laughable. Of 242.4 billion Swedish crowns ($22.1bn) in payments made by the Social Insurance Agency in 2023, some 2.2 billion were paid due to fraud—a rate of 0.9%. Obviously, the 2.2 billion figure is widely reported. This very low percentage is not. One wonders if a new government agency to prevent the widespread fraud evidently plaguing Swedish society is the best use of public money. I thought the budget was as tight as it was.

Policies of coercion are not working; Sweden has the fourth-highest unemployment rate in the EU. Cutting welfare does not create jobs. If anything, lowering the purchasing power of citizens decreases jobs because companies will not make products for non-paying customers. Moreover, individuals losing their welfare while trying to enter the workforce will not suddenly become more motivated. In many cases, they will suffer mentally and physically, as did Chermaine Leysner.

Sweden’s government budget for 2025 offers a clue as to what is really going on. Tax cuts worth some 13 billion crowns for people with high salaries have been announced, creating around 1,700 jobs, according to the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO). However, LO economists estimate that the money could have funded over 16,000 jobs through public spending. Curiously enough, a government walking The Work Line is actively choosing to create fewer jobs.

Economic programmes favouring the rich do not incentivise people to work. They do the opposite, creating less empathetic, more ruthless societies. By continuously slashing taxes for the wealthy, inequality has reached a point where work does, indeed, not pay off. For example, Hugh Grosvenor, now the seventh Duke of Westminster, inherited over £8 billion and did not pay a penny in tax. For an ordinary working person to achieve this level of wealth is impossible. Low capital gains tax also ensures that those already invested have a near insurmountable lead.

It is all connected. Political choices to favour tax cuts and private outsourcing over long-term investment have decreased states’ capacity to honour their part of the social contract. With less money available, people are quick to identify individuals on benefits as villains since they have been framed as a burden to society. Systems constructed with a negative view of human nature thus become the logical response, further excluding vulnerable groups, mainly immigrants and low-income individuals.

A less cohesive society breeds animosity. Enter Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen and the rest to channel grievances for their own purposes.

Humans are not selfish. We are naturally cooperative and altruistic. Ample research supports this assertion. To claim otherwise has been used to justify the hyper-individualistic, celebrity-obsessed culture we are currently living in. People want to contribute, and they try their hardest to do so. Those who cannot should be supported, not punished. If the goal is inclusive, democratic societies, the carrot is always better than the stick.

// Adrian

Cutting costs should never be prioritised over human dignity 👏