Stephen A. Smith and Everyday Libertarianism

Everyday libertarianism legitimises a reduction of responsibility for individuals and corporations to care about nothing but themselves.

One of the more shocking pieces of news during my summer hiatus was the sudden departure of legendary sports writer and commentator Skip Bayless from his show Undisputed on Fox Sports 1 after eight years. Before joining FS1, Bayless spent over a decade at the ESPN TV network, where he is most known for having co-hosted the debate programme First Take with Stephen A. Smith—another esteemed sports journalist.

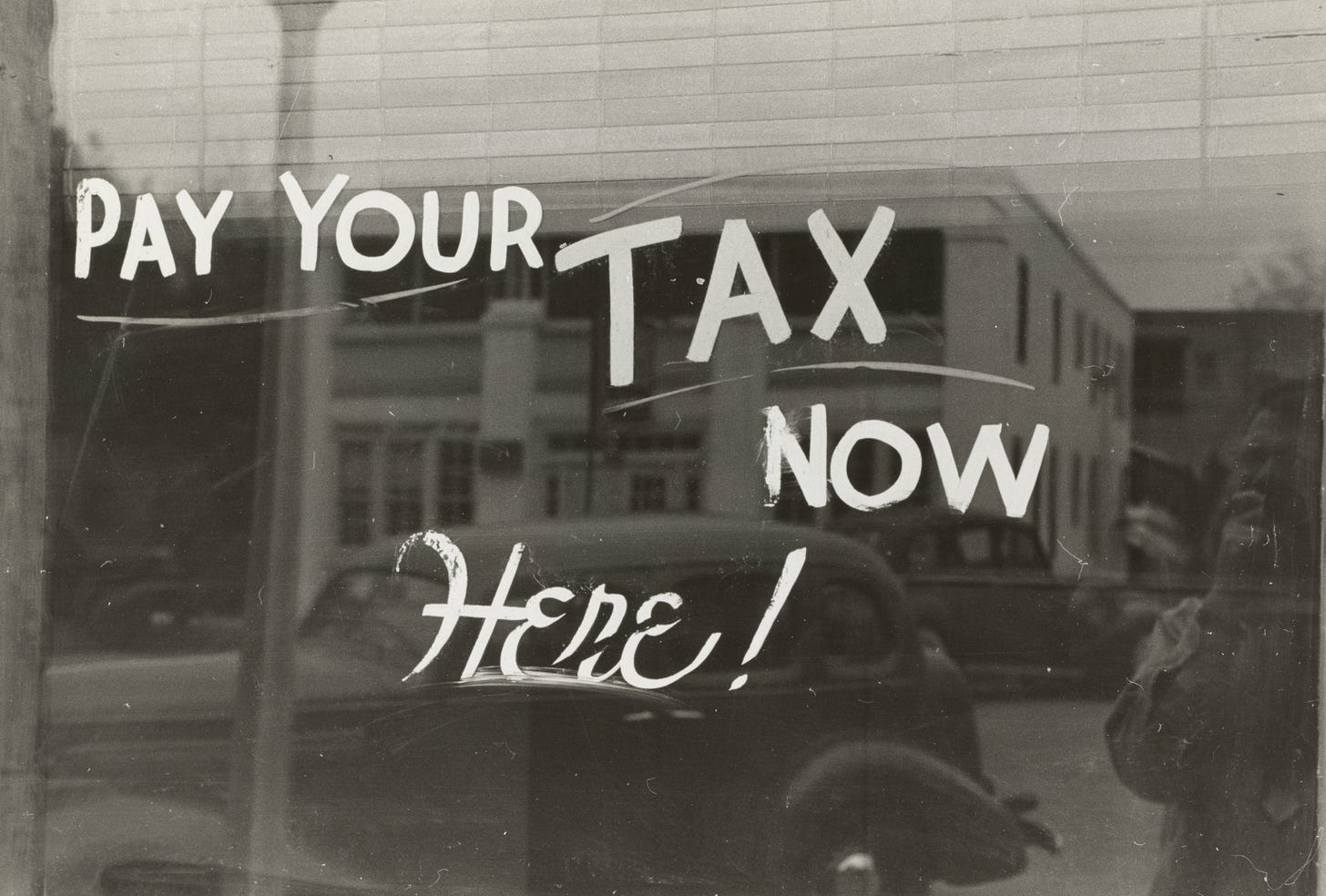

First Take is still going strong with Smith at the helm. It’s the most-watched morning sports show in the United States. Recently, when discussing basketball star Klay Thompson’s choice of free agent destination—which team he would sign with now that his current contract has expired—Smith asserted on his podcast that Thompson made a good choice choosing the Dallas Mavericks because of their coach, the makeup of the team and perhaps most importantly because Texas has a 0% state income tax. This was especially attractive because Thompson had played in San Francisco, California, for the past several seasons, where taxes, according to Smith, are way too high.

When lamenting over the high tax rate in California and elsewhere, Smith is voicing a popular sentiment: that individuals and corporations somehow are entitled to their entire pre-tax income, that the state is taking something that doesn’t belong to it.

In their 2002 book The Myth of Ownership, Liam Murphy and Thomas Nagel argue that individuals do not inherently deserve property because there is no natural right to property. What people own is, in an advanced economy, determined by the legal system: by the state. Government laws and regulations are necessary for a market system to function and be profitable for the actors operating within it. To keep this system in place, the state levies taxes on individuals and corporations, which would not have any income if it were not for the state. In other words, there is no fair or natural tax system in a modern economy.

That people think they have an innate right to their money is part of a perspective Murphy and Nagel call everyday libertarianism—a set of assumptions that stem from libertarian ideology and are based on the view that pre-tax market outcomes are the natural state of affairs before government interference.

The claim to fairness under libertarianism is that individuals who contribute more should earn more money. As philosophy professor Robert Young wrote in a piece critiquing The Myth of Ownership:

“[C]ontrary to what Murphy and Nagel contend, it does not seem incoherent, for example, to hold that, other things being equal, if A and B expend quite different amounts of effort on a productive task, and A produces more that is beneficial than B, that A deserves to have more of the property produced than does B.”

Did you notice? “Other things being equal.” The issue is that things in the real world are not equal. First, in a modern economy, the amount of effort expended is not what determines remuneration—American CEOs make, on average, 196 times more than their workers and executive pay rises keep outpacing employees. Second, to get a stable job that earns a wage outrunning inflation, one needs the financial and social stability to pursue an education and possibly work as an unpaid intern. Third, wealth inequality ensures that some people have it far easier to land positions of power and status, entrenching a sense of a natural order of things, including today’s “fair” tax rate.

In fact, taxes are needed not only to keep the economy going but also to make societies more cohesive via resource redistribution. More equal countries are generally healthier, happier, more creative and educated, and less violent. Moreover, research shows that, historically, states extracting much of their revenue from taxation tend to be democratic and accountable to their citizens. Those acquiring sufficient capital from other sources—such as elite groups and natural resources—tend to be more authoritarian. To even the playing field is to be democratic.

It’s important to note that this is not saying taxes need to be high for everyone, or that tax rates have been perfect in the past. Famously, Swedish author and Nobel laureate Astrid Lindgren had an effective tax rate of 99.75% in 1976. This number is, obviously, absurd. But there needs to be a happy medium, especially for very rich people like Lindgren.

The same logic applies to corporation and wealth taxes. One could argue—I don’t agree—that firms paid too much tax in the decades before 1980. The situation right now, however, is untenable. To name but two examples: At least 55 of the largest firms in the United States, including FedEx and Salesforce, paid no federal income tax in 2021. The same year, seven tech firms were estimated to have dodged £2 billion in UK taxes.

To talk about wealth taxation, meanwhile, remains a political suicide mission. Such pushback is surprising given that a mere 2% levy on individuals in the UK who own assets worth more than £10 million—applicable to 0.04% of the population—would raise up to £24 billion a year. For reference, that’s 11% of the NHS total budget for 2022/2023.

These are not communist policies. They are necessary to ensure a functioning democracy where everyone feels invested in their country’s future.

Now, let’s examine California—a land where the taxman reigns supreme, according to Stephen A. Smith. While it is true that the Golden State has a higher income tax than Texas, for example, its system is progressive. Those with higher salaries pay more than individuals with lower incomes, impacting, among others, NBA players and nationally broadcasted sports commentators.

The opposite is true in Texas. Texans earning less than $22,000 pay a larger share of their income in state and local taxes than the 1% of Californians earning over $862,000 annually. Is that “fair”?

It is rather fitting that Smith, a man who doesn’t see the societal value in paying taxes, believes Michael Jordan to be the best basketball player of all-time and subscribes to the narrative around him. As the mythology goes, MJ, by sheer completive grit and skill—with a little help from Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman—managed to win six NBA championships in eight years, winning Finals MVP each time and remaining undefeated in final’s series over his entire career. Undoubtedly impressive.

What’s conveniently left out is that His Airness played 15 seasons in the NBA and had one of the best coaches ever, an excellent general manager assembling his teams and thus great teammates beyond Pippen and Rodman. For example, John Paxson scored 10 points in the final four minutes of Game 5 in the 1991 finals and hit the game-winning shot to secure Jordan’s third title in 1993. All this in an era where players didn’t often change teams. If your basketball club drafted a good team, which is easier if your organisation is well-managed, it had a decisive advantage. The structural factors benefiting MJ are seldom considered when assessing his success or comparing him to other great players.

The story of a hero overcoming all odds and becoming successful by keeping his head down and working hard is part of the American Dream, a sickness which has spread to all corners of the world through Netflix and JPMorgan Chase.

Assumptions of everyday libertarianism are dangerous because they legitimise a reduction of responsibility for individuals and corporations to care about nothing but themselves, to prioritise profit above all and to forget how those gains are obtained through collaboration—to the detriment of society. Democracy does not work if people do not believe in its merits. And, by the way, LeBron James is the GOAT basketball player.

// Adrian

Tack för intressant läsning!! // Maja Ekman