Steak au Poivre in Cairo

Russia and China spread disinformation to divide societies, but most fake news circulated online has domestic origins. Why?

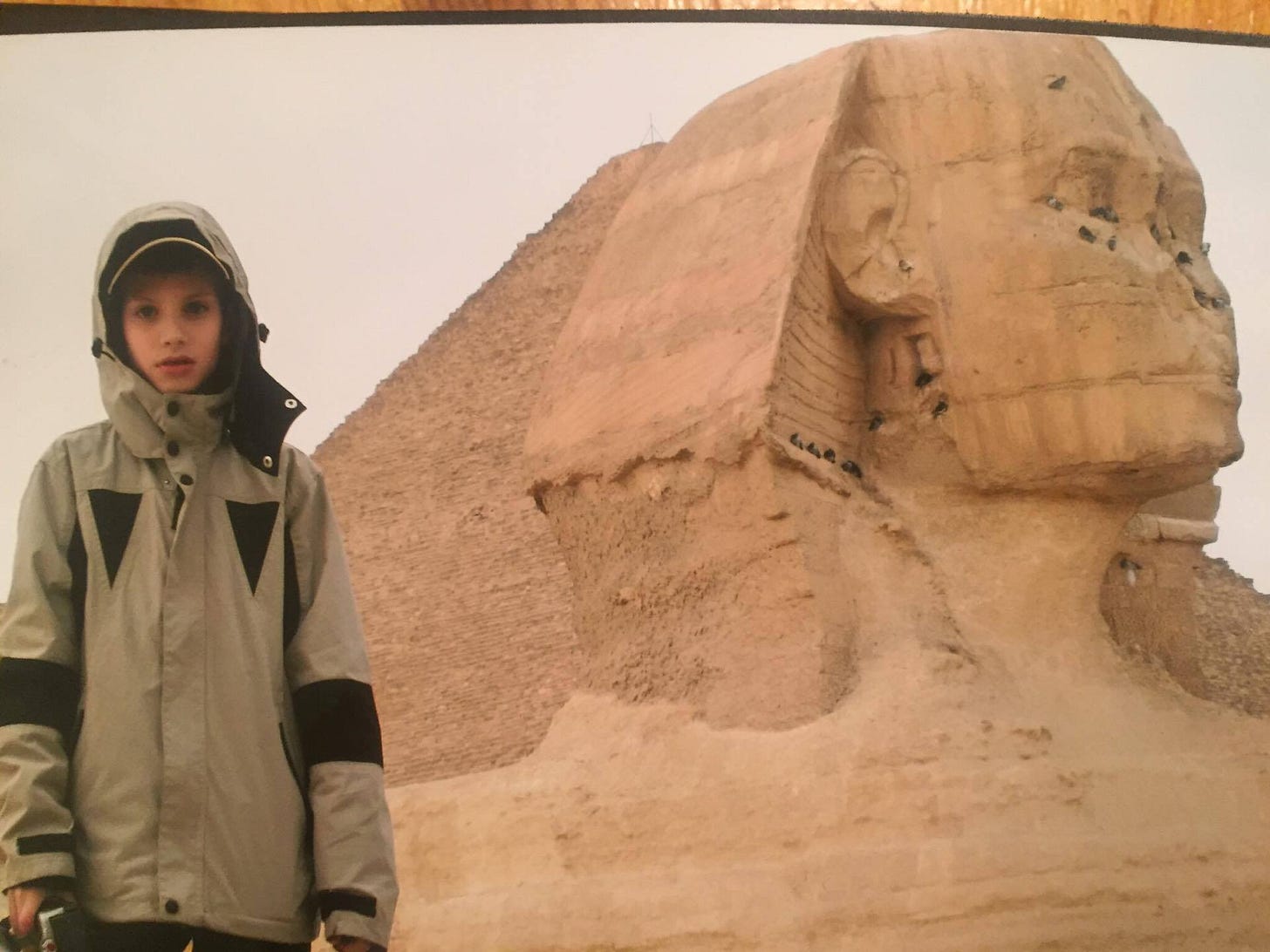

My father and I went to Cairo, Egypt, in 2008. I was nine, and I don’t remember much except for the grandeur of the pyramids, how small the Great Sphinx is and that I had steak au poivre at the hotel restaurant for breakfast and dinner every day. I would’ve had it for lunch, too, but holidays outside a resort require one to leave the hotel for at least a few hours.

So vivid is my memory of this pepper-crusted beef—and the accompanying peppercorn sauce—that I recall having it at the restaurant bar seated on a steel bar stool of the single-legged variety, drinking Coca-Cola while my dad enjoyed a Sakara beer; it was one of his favourites, I think.

It’s funny how late at night, or any time of day if you feel better, recollections of certain events can enter the mind and trigger specific feelings. For me, the memory of eating steak au poivre in Cairo 16 years ago always elicits warmth and anticipation—I was still to go on many trips with my father, eat food in other hotel bars and admire sites which would all be compared in stature to Khufu’s great tomb.

One day, after breakfast, we went to Alexandria. I remember visiting the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a modern homage to the ancient Library of Alexandria, one of the largest of antiquity. Opened in 2002, it has shelf space for around 8 million books and is a fine example of contemporary architecture. I didn’t know this then, obviously.

Looking back, what I find most striking about my excursion to the city is that, a few blocks away from the library, in the Sidi Gaber neighbourhood, Egyptian police would in June 2010 murder 28-year-old Khaled Said. Photos of his disfigured corpse were shared online, and the outrage helped incite the Egyptian popular protests of 2011, resulting in the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak.

The Egyptian people’s toppling of Mubarak, who had ruled the country since 1981, was part of a series of protest movements and uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa between 2010 and 2012 known as the Arab Spring, ousting regimes in—other than Egypt—Tunisia, Libya and Yemen, and leading to civil wars in the latter two as well as Syria.

Amid the upheaval, in 2011, Time Magazine named “The Protester” its Person of the Year. In the issue’s introduction, Richard Stengel, then-Managing Editor, noted: “Social networks did not cause these movements, but they kept them alive and connected.”

Indeed, many scholars and commentators in the wake of the Arab uprisings praised the Internet’s capacity to bolster protests and advance democracy (see also here). In Egypt, the Facebook page created to spread the images of Said quickly gained over 100,000 members, and research shows social media was instrumental in coordinating the demonstrations.

The Internet optimism of the time was expressed succinctly by British politician Timothy Kirkhope in an opinion piece for The Independent in 2012:

“The internet allows for greater freedom of expression, facilitating citizens’ ability to challenge and criticise: a basic democratic right. These social media sites [Facebook and Twitter (X)] also have the power to actually bring democracy about - the Egyptian Revolution 2011 being a prime example.”

Today, the tone is quite different. The belief in the Internet as an agent for progressiveness has been replaced by a conviction that the medium undermines democracy.

Russia and China use their armies of trolls, bots and hackers to influence US and European affairs, decreasing trust in Western political institutions. For instance, in March (2024) pro-Russian accounts were discovered pushing anti-immigration narratives to manufacture support for Donald Trump’s presidential bid, akin to the Kremlin’s strategy in 2016. Meta, in November last year, stopped a network of almost 5,000 accounts created in China aiming to deceive American voters. In Europe, there are similar examples.

The spreading of fake news can have a real impact, and 87% of people in a global Ipsos poll believe it has harmed politics in their country.

To contrast just how much the mood has changed since Kirkhope’s assertion, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, recently said the EU, if she’s reelected, will combat the spread of disinformation online by putting forward a “‘European Democracy Shield’...that focuses on the biggest threats from foreign interference”. In other words, to protect democracy, information flows on the Internet need to be curtailed.

This outlook might be correct, and Russia and China do spread disinformation to divide societies. But the alarmist sentiment misses a crucial point: Putin, Xi and their security apparatuses are not omnipotent. Much of the false information circulated online in Western countries has domestic origins.

It was Internet trolls employed by the far-right Sweden Democrat party that spread online hate in Sweden; Spanish Facebook accounts claiming 97% of people of the country’s minimum basic income are immigrants; Polish TikTok users saying Ukrainian immigrants were raping local women; US social media users spread the message of “the Big Lie”, that Biden had stolen the 2020 election. And so on. The call is coming from inside the house.

The next question is why people in the West are susceptible to these kinds of narratives. Russia and China cannot create internal dissent out of thin air.

In the United States, for example, research shows that groups such as the Koch network of extreme-right donors and its allied organisations have, with great success, adopted disinformation tactics to transform institutions and the legal system in a hardcore libertarian direction (see also here). This has, in turn, led to decreased trust in government, political parties, political institutions and traditional media.

Another issue is the economic system pushed by the Kochs and their peers. Stagnating wages, increasing inequality and a general decline in living standards for the working and middle class, including decreased life expectancy, have American voters seeking answers. Such a trend is visible in Europe, too. The UK is in decline, and inequality is growing alarmingly across the continent. 15 years of austerity policies have done nothing but reduce living standards and resulted in underinvestment for the future.

As a reconsideration of economic structures is seemingly off the table for discussion, simple narratives based on nationalism and xenophobia become increasingly disseminated and compelling.

People have the right to be angry. The current system is not sustainable. While those in power pretend it is and blame Russia and China for manipulating their citizens, parties and leaders who appeal to anger and fear will dominate, and the Internet will play a crucial role.

United with the discontented populations of Europe and North America by virtue of their common humanity was the people of Egypt in 2011, who, as per their slogan, wanted “Bread, Freedom, Social Justice and Human Dignity”. Their example is a powerful reminder that people can come together and demand change based on maxims eschewing bigotry and hatred. Ultimately, they were unsuccessful, but not for lack of trying.

Myself, my father and our taxi driver, Mohamed, returned from Alexandria towards the evening. I first met Mohamed a few days earlier when he took us from the airport to the hotel, after which Dad hired him as our exclusive driver for the week—a weird yet not uncommon arrangement during our trips abroad. Once dinner at the hotel bar had been devoured, I went to bed. Full and exhausted. Outside, a storm was brewing.

Hi. Loved the article and also your picture next to the Sphinx. Keep them coming.

Hands down your best piece yet