Europe’s Economic Dilemma

Since the Financial Crisis, private capital has failed to spur long-term growth in Europe.

Former Italian Prime Minister and President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi released a report some time ago assessing the economic future of the European Union. The almost 400-page document is unequivocal in its thesis: the EU risks falling further behind China and the United States economically, with the bloc facing an “existential” problem unless it heavily increases investment in industry and public goods. It’s about time Europe realised that all costs are not the same.

The situation wasn’t always as dire. In 2008, Europeans, in aggregate, earned 10% more than their US counterparts. By 2022, Americans earned 26% more than Europeans.

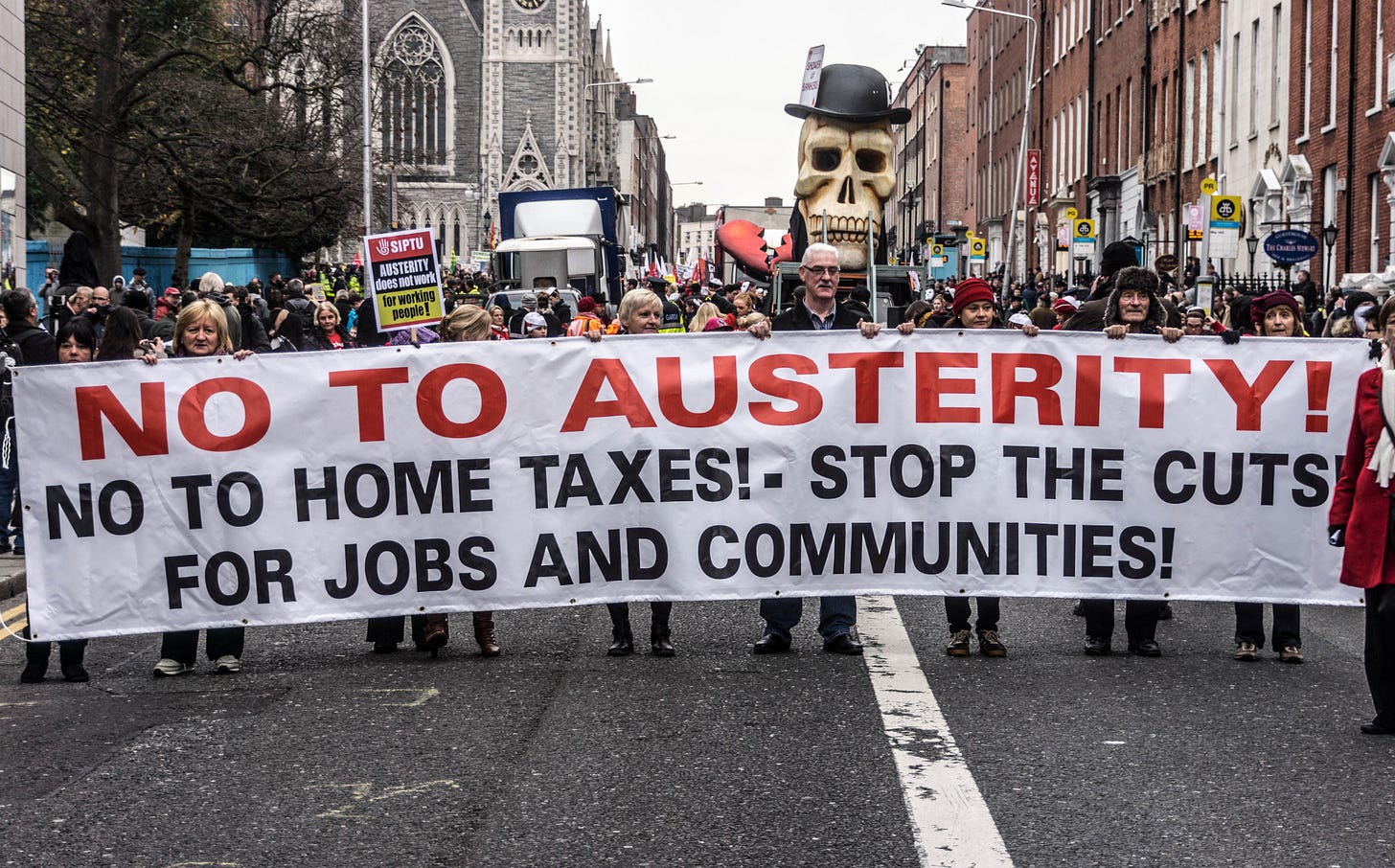

Then came the 2008 Financial Crisis, which saw European countries implement aggressive austerity measures—governments cut spending and borrowing to get budget deficits under control. Sovereign indebtedness had spiralled for several reasons, but the root cause of the crisis was that the financial sector, fully unshackled, had lent too much money to people who could not pay back. The bailouts needed to save the banks of Iceland, Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal were costly.

In the heat of battle, the EU put in place regulations to define the limits of public spending and borrowing, including a reinforcement of rules to bring government deficits under 3% and debt/GDP ratios under 60%.

Intuitively, such an approach might seem logical. Much like a household or an individual needs to cut expenditure and save when falling on hard times, a country should do the same. The issue with this reasoning is that a 21st-century nation-state is nothing like a person or family.

In any economy, collective expenditure equals collective income—meaning reducing public spending lowers an economy’s overall size. Moreover, to cut government expenditure at a time when private spending is already waning due to an economic crisis will exacerbate the declining of total income and worsen the recession.

In this environment, investments in fixed assets growing the economy long-term are disincentives for two main reasons. First, private companies will not invest in the capacity to make products if consumers do not have any money to buy them. Second, the budget post for public investment and research and development (R&D) is one of the first to decrease during austerity. Indeed, government investment across the EU has remained subdued since 2008.

Europe is still living with the consequences of austerity. Research shows that the policies implemented during the crisis have made citizens €3000 a year worse off. Governments would also spend €1000 more on public and social services per person if austerity had not been imposed. Ireland and Spain have been particularly impacted—average incomes dropped by 29% and 25% between 2008 and 2022. Across the continent, Europeans are becoming poorer, especially compared to the US.

The European Union is estimated to have a €5.4 trillion investment gap for 2025–2031. To bridge it, the private sector and member states need to contribute. Unfortunately, austerity has lowered private demand by making people poorer, discouraging firms from investing in future output. As for governments, the EU keeps insisting on strict fiscal rules, regardless of their impact on public investment capacity. These processes create a vicious cycle of stagnation and make it harder for countries to reach climate goals by stifling investment in green technology.

In what can only be described as a Kuhn-loss of the highest order, those with power and influence have learnt the wrong lessons from the past 16 years. Benjamin Dousa, Sweden’s newly appointed Minister for Foreign Trade and International Development Cooperation, concluded the following when assessing Europe’s stagnation problem:

“[T]he Commission expects that state-sanctioned and subsidised industrial policy will solve our problems. Politicians have never managed to pick winners effectively before, so why should they succeed now?”

Looking at the EU’s current predicament and deducing that what’s needed is not a coordinated government response to energise the economy is baffling. Since the Financial Crisis, private capital has failed to spur long-term growth in Europe. Firms have collected high profits instead of investing.

Why shouldn’t they? Not only are Europeans poorer, but companies in our current political economy are conditioned to only work towards short-term profit maximisation, lest the share price not grow following the Value Creation Plan. The model Mr Dousa is advocating for is the one currently in place—yet he seems unsatisfied.

Neglecting the state’s crucial role in economic development and the refusal to accept that trickle-down economics does not work are Neoliberalism’s biggest ideological shortcomings. And while under the doctrine’s spell, it is hard to break the cycle of decline. For example, a government can, as explained above, increase its spending to stimulate the economy. This, however, is unthinkable as the dogma says such an intrusion in the marketplace will crowd out private investment—which is always more effective than public money. (Never mind the empirical evidence). When adding the EU’s fiscal rules, you get a perfect storm.

The neoliberal obsession with austerity and shrinking the state as a matter of principle leads to a misinformed reading of public finances; some costs are better than others. There is a difference between spending taxpayer money on high salaries for municipal politicians and investing in things that can grow the economy, be it infrastructure, education or healthcare.

Ironically, the United States has figured this out. The Biden Administration has passed legislation pouring trillions of dollars into R&D, green technology, healthcare subsidies, infrastructure and much more—most notably through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Consequently, the US economy is growing, as the European commentariat likes to point out.

// Adrian